Sal Davis: The man who brought the roaring 60s to swinging Dar

By MOHAMED SAID

| Sal Davis at Chef Pride Lumumba Street |

I HAVE BEEN LIVING IN TANGA for the past 10 years but I come to Dar es Salaam each month, and to keep abreast of news in town I have my baraza. We people from the Coast have places where we meet for a palaver — street corners were we sit down in the evenings to talk and relax over a cup of coffee. We call them barazas. It is an old custom of the Coast going back many years. Africans being male chauvinists, the baraza is strictly a male affair.

Since we are now adults, we no longer frequent the street corners, which have now been taken over by the young generation.

In addition, there is no parking space. The Dar es Salaam of 2000s is not that of 1960s. There are today no respectable places in Dar es Salaam, particularly in Kariakoo, where one can hang out. The high-rise buildings have completely changed not merely the scenery but also the atmosphere, customs and traditions. My baraza is now a restaurant, Chef’s Pride, where I go for a cup of tea or for snacks.

One day I was sitting talking with my friends at our baraza and there suddenly standing in front of my table facing me was none other than my childhood idol — Sal Davis. There was no way I could mistake the man. Four decades had passed since I last saw him. My mind raced back. I stopped speaking and stared at him in disbelief.

Standing there was a white haired version of Sal Davis, the man whose songs I had sung as a kid. A flood of memories swept over me. I could remember exactly where I was when I first heard Sal Davis singing Makini over the radio. It was at the house of my uncle, Bwana Humud, on Kipata Street (now Mtaa wa Kleist). This was 1963 and I was 11 years old. The flip side of Makini was the song Ayayaa Uhuru, which Sal Davis composed to honour Kenya and Zanzibar’s independence as both countries, got their independence in 1963. (The government banned Ayayaa Uhuru in 1964 after Zanzibar’s revolution because the lyrics mentioned Mohamed Shamte, the first prime minister and other patriots in the first Zanzibar government before the revolution).

As I sat there gaping at Sal Davis, these thoughts racing through my mind, a friend, Mahmud, broke the spelll, “Mohamed, let Sal Davis be! Let us go on with our story. You were saying?” That brought me back from the early 1960s to the present time. “No, Mahmud, do not talk like that! This is Sal Davis, my childhood hero. I used to sing and dance to his music when I was very little.” Sal Davis, surprised by my outburst and that generous introduction, held out his hand to me.

MY EARLIEST CHILDhood association with music goes back to the mid 1950s, to the house of my aunt Bibi Mwanaisha bint Mohamed on Livingstone Street in Dar es Salaam. Closing my eyes, I can still see her putting my favourite song on her gramophone: El Sonero by Sexteto Habanero, and calling to me, “Mwamedi (a corruption of Mohamed), now show them how to dance!” I was four or five years old. My aunt would clap her hands in time with the music to encourage me. I would stand up and dance and there would be much laughter.

(Sexteto Habanero was a group from Cuba whose music was very popular in the 1950s, featuring regularly on radio Sauti ya Dar es Salaam, which began broadcasting in Tanganyika in 1951.)

I liked that gramophone so much that my aunt used to tell me it was going to be my wedding present. I remember when my aunt had to take the gramophone to another house, say for a party, she would wrap it in a bed sheet and carry it balanced on her head. The records would be stored carefully in a basket. Slowly, I picked up the songs, which were in Spanish, and began to sing them, though I could not understand the meaning. The earliest songs I learnt were therefore not in my language – Kiswahili — nor were they kid stuff but Spanish dance music numbers. I do not know if this had any influence on my taste of music in later years when I came to appreciate the music of Nat King Cole, particularly the songs he did in Spanish like Cachito Mio.

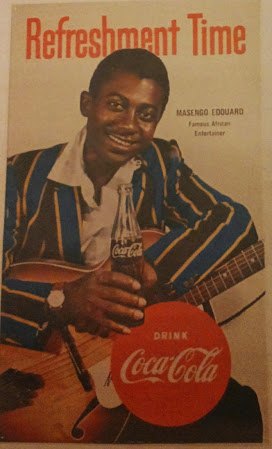

When I started school, the radio replaced the gramophone in my affections; through this medium, I was now able to listen not only to the music of Salum Abdallah, John Mwale, Eduardo Massengo, Mwenda Jean Bosco and others but also follow the comedies of Mzee Pembe and other entertainers. I am today the proud owner of a CD of Sexteto Habanero titled Sexteto Habanero 1926 – 1931 (a gift from my friend Dr Harith Ghassany) that contains the song El Sonero that I used to dance to 50 years ago.

|

| Masengo Edouard |

| Salum Abdallah |

| Eduardo Massengo

As a young boy in the Dar es Salaam of the 1960s, I was immersed in the period people of my age call the Roaring 60s. This was the era of Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard, the Beatles, Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones, Eric Burdon and the Animals, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Helen Shapiro, Connie Francis and so on. Woodstock came much later in 1969, bringing to our attention Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Ike and Tina Turner etc.

|

The soul music of James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, Tom Jones, Aretha Franklin, Sam and Dave and others came much later.

In those “good old days,” Saturday was the day for movies – the afternoon shows at Empire Theatre. Our favourites were westerns and musicals but not Julie Andrews’ The Sound of Music and that type of stuff. We went in for pop music movies — The Young Ones and Summer Holiday starring Cliff Richard, Love Me Tender and Jailhouse Rock starring Elvis Presley. We loved pop music because we were young and we loved to shout and sway in our seats when Cliff or Elvis was singing hot numbers. You just cannot shout when Julie Andrews sings My Favourite Things accompanied by a full orchestra. The most one could do was to doze off.

The first Elvis movie I saw at Empire Theatre was Blue Hawaii, on Eid ul Fitr day in 1964. This was to be the start of my attachment to Elvis, which lasted until he passed away in 1977.

There was no song by Elvis that I could not sing. I remember when I got home my father had already retired. Eid day was the only time I could be out at night with my friends. The following morning, as we were having breakfast, my father listened patiently to my Elvis stories, then told me that in his time his idol was Bing Crosby. That was when I heard of Bing Crosby for the first time. (Years later, visiting Ambassador Abbas Sykes, a contemporary and childhood friend of my father, I came across a video cassette of the movie High Society, starring all my father’s idols — Bing Crosby, Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra and Grace Kelly. Noticing my interest in the video, Abbas Sykes told me, “I walked from Kipata Street to Avalon Cinema with your father to watch that movie.”)

We also went to Empire Theatre to watch Billy Fury and Helen Shapiro in Play it Cool. In the movie, Helen Shapiro sang I Don’t Care, a song that many girls in Dar took as “their” song. When she made that movie, Helen Shapiro was about 14 years old, slightly older than me at that time. Many years later as a student in Britain, there was a café I used to frequent near Liverpool Coach Station, London. At this café one afternoon, I saw an advertisement announcing Helen Shapiro as a born-again Christian. She was a member of the Jesus for Jews Movement. What a transformation.

But looming larger than any of these international stars in the days of was our very own Sal Davis. Sal Davis had a special place for me and for most of us of that generation. He was our homeboy. Based in London in the 1960s, Sal Davis was the only star from East Africa to acquire international fame and popularity as a singer and composer. Young as I was at that time, listening to his early numbers like Poor Little Rich Girl, or Mama You Treat My Sister Mean or Unchain My Heart, to mention only a few of his hits, we were astounded.

His “authentic” accent, the orchestration, the chorus girls in the background? for most of us, it was not initially easy to tell whether Sal Davis was black or white. It was only when Makini, was released, with its mixed Kiswahili and English lyrics, that his identity was revealed to me. I was surprised to learn that his name was Salim Abdullah Salim.

That was many years ago. Sal Davis changed his name to acquire one that went with the trade. Maybe he thought the name was just too much of a mouthful for English fans and would sound and look out of place on billboards and record labels. The song Mama You Treat My Sister Mean makes me recall my childhood friend Abdallah Rugome, now deceased. The song was his personal favourite, which we used to sing together —immediately after finishing “his song” I would start in with “my song” — Poor Little Rich Girl and Abdallah would join in. Abdallah adored Sal Davis so much that he tried his best to sound like him. Today when I talk to Sal Davis and listen to the way Sal Davis speaks I see my late friend Abdallah Rugome standing there in front of me.

| Sal Davis in Germany in 1960s |

SAL DAVIS ONCE PERFORMED in Dar es Salaam with Chipukizi Club. This was an elite music group of talented boys and girls still in school. They used to record a music programme with Tanganyika Broadcasting Corporation that was very popular among the youth. When Chipukizi were on the air, none of us would be in the streets. The signature tune, which introduced Chipukizi on the airwaves, was a song titled Here We Go Loo Be Loo.

“Here we go loo be loo, here we go loo be loo, Here we go loo be loo on Saturday Night?yeah, yeah?”

The Chipukizi members were very young, most being in their teens and still in school, but their music was beyond was ahead of the times. I was not of age and therefore remained a distant admirer of the Chipukizi Club.

When Sal Davis came to Dar es Salaam and recorded a programme with Chipukizi, I remember that he sang The Moon was Yellow and the Night was Young. That show with Sal Davis was the pinnacle of Chipukizi Club’s career; soon after, Chipukizi Club was off the air, banned for political reasons. The young boys and girls were not portraying the image of the youth Mwalimu Julius Nyerere was trying to project.

The vacuum left by Chipukizi was soon to be filled by new groups like The Rifters, The Sparks and The Tonics and the afternoon “boogies” at the Arnatouglo Hall, which we sometimes called the Sunday School. However, these groups did not have the elegance of Chipukizi. While Chipukizi was elitist, these new groups were sort of “free for all.”

Chipukizi inspired me to pick up the guitar. I had excelled in playing the flute and mouth organ. I could play all the Kwela songs by the legendary Spokes Mashiane. However, it was the music of stars like Sal Davis that exerted the greatest influence on me. Many young boys at that time who played the guitar tried to copy the style of Hank B. Marvin, lead guitarist of the Shadows, the group which backed Cliff Richard. Dar es Salaam was not short of talent.

There was the late Adam Kingui (the Rifters) Abby Sykes (the father of Dully Sykes the Bongo Flava artist), George Muhuto (The Sparks), David Gordon (of the Safari Trippers, who introduced me to the music of Eric Clapton, the British blues guitarist), and others. Hank B. Marvin liked to play open strings mixed with high pitch picking right at the back of the guitar just behind the pick up, thus producing a peculiar sound.

|

| Adam Kingui in 1965 |

It was many years later when Hank Marvin had faded and guitarists like Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana, Jose Feliciano and others came into the scene that we also bent with the wind of change. I personally strove to emulate the jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery but with little success, for no one can play the guitar the way Wes — a slow melodious riff using all his fingers before switching octaves midway or in the last part of the song.

Some few years ago, I met Salum Hirizi, a former member of Chipukizi, in Dubai and we got down to talking of our days growing up in Dar es Salaam. Salum married his childhood sweetheart Amina. Their son, Abdullah, a teenager, was surprised to hear that his old man used to be a singer. He asked me, in English with a London accent, what kind of songs his father used to sing. I told the boy that whenever I think about his father, the song Summertime comes to my mind.

| Salum Hirizi (Hariz) in 2013 |

THERE AND THEN, THAT evening at Chef’s Pride, Sal Davis and I became friends. It turned out to be an evening to remember. The boy long buried inside me took hold. I would pick up one of Sal Davis’s songs and begin to sing and before I could finish the first stanza Sal Davis would take the song from there and sing along with me? We went on like that for quite some time. A one-sided wrestling match of sorts. It was not even a duet, for I wanted to hear Sal Davis singing to me. We sang Unchain My Heart, Don’t Leave Me, of course Poor Little Rich Girl, I am Branded and we sang songs by other artists that were hits in the 1960s.

My friends were astounded. These were people who had known me as a grown up and had no knowledge of my background in music. Everyone was remarking, “Oh, Mohamed! We did not know you were into music.” I teased Sal Davis, telling him if he dared invite me on stage, I would outshine him.

Here I was, an upstart whose music had never gone beyond the four walls of my little room, singing along in a café with the famous Sal Davis. Sal Davis who had shared the stage with music greats of his time like Shirley Bassey and Cliff Richard. As a parting shot, I sang Those Were the Days by Mary Hopkins. Oh, it was unbelievable; Sal Davis did not even wait for me to finish the first line before joining in.

It turned out that Sal Davis was in Dar es Salaam with a contract with Kilimanajro Kempinski Hotel, where he performs with his band. He also has his own show on Clouds FM.

Back home that night, as my wife was laying the table, I told her, “You will not believe this! Today, I sang with Sal Davis!” To my astonishment, back came the reply, “Who is Sal Davis?”

Sal Davis at Nairobi Air Port 1963 Returning Home to Kenya

for Independence Celebrations of which he Composed a Song ''Nyimbo ya Kenyatta,''

Sal Davis Listening to the Song watched by Phillips Manager

Sal Davis Listening to the Song watched by Phillips Manager

Mohammed Said, a political scientist based in Tanga, works as a marketing officer with the Tanzania Ports Authority and is the author of The Life and Times of Abdulwahid Sykes 1924 - 1968 (Minerva Press, London 1998, serialised in The East African in January 1999) and Torch on Kilimanjaro (Oxford University Press, Nairobi 2006)

No comments:

Post a Comment